Indie Game Project: Peninsula (2)

I have engaged mainly in programming from the beginning of the project. The fact that I am a professional software engineer is not the only reason contributing to the focus on programming; rather, it is attributed to my belief that programming is what actually decides what a game will look like. Programmers are not mere implementors of specifications suggested by designers, but they rather actively determines the overall structure of games and directly influence the players’ gameplay experiences.

There is no panacea that covers all the games with different genres and platforms. Peninsula is a real-time tactics with 3D, top-view, and multiplayer system targeted for mobile. These characteristics have determined the today’s appearance of the project code. Peninsula is being developed using Unity and C#, Mirror framework for mobile, and other libraries either purchased from Asset Store or crafted on my own.

As stated in the previous post, Peninsula is aiming for commercial success and is not a demo for showing off my skills. This philosophy is best demonstrated through the reasonings behind the code of the project. Basically, I have constructed the project following predetermined coding rules and practices. Moving one step further, the overall structures are also fine-tuned in order to enhance software maintainability and scalability. Although the codebase is expanding beyond the average scale of a personal project, planning and following principles have facilitated the continuous growth of the project.

This article introduces not only the overall structure of the game as a software but also my beliefs and attitudes toward software engineering in general. Along with other posts introducing modules and techniques, you will be able to grasp which objectives the Peninsula project has been striving to accomplish.

Programming in Peninsula

Development Environment

Game Engine - Unity

Nowadays, there are numerous game engines with their own strengths, but the leading engines occupying the market are Unity and Unreal. I opted for Unity over Unreal for its suitability for an indie project. Compared to Unreal, Unity offers a simpler interface, vast asset store, and supportive community, streamlining development for a solo endeavor. Unreal’s power is undeniable and overwhelming that of Unity when it comes to AAA projects. Nonetheless, Unity’s ease of use and cost-effectiveness better suit the scale and resources of my indie venture.

I admit that the emphasis is solely focused on the easiness of carrying on the project on my own. But here is a lame excuse. During the development process, I have just encountered a malfunction with which figuring out what the root cause is or even diagnosing the problem is hopeless. If I belonged to a large team and were cooperating with other programmers, it would be possible to ask them for a solution and get some help from them. In this case, however, I am the only developer of this project, so I can only google the keywords, hoping someone has asked the same question and another one has replied with a relevant answer.

Unity boasts a large community where users with different backgrounds share their knowledge and debate about various topics. Unity Forum is a community officially managed by Unity Technologies, where you may find exactly the same solution to your issues or post your own question if you end up finding no suitable one. Of course, Unreal has an analogous community named Unreal Engine Forum, too, but due to the nature of large teams rarely sharing their know-how externally, the volume of accumulating information is unparalleled.

Aside from the accessibility to a large solutions pool, Unity offers another attractive point when it comes to its scripting language: C#.

Programming Language - C#

C# is a general-purpose, high-level, managed programming language designed by Microsoft. Some key features of C# are Object-Oriented Programming (OOP), static and strong typing, generic, and metaprogramming [2].

The most significant reasoning behind C# is pragmatism. Contrary to C++, a (relatively) low-level unmanaged language that carries a bunch of heritages from ancient days, C# was designed from the ground, thus accommodating diverse demands from users and being capable of polishing the language rapidly up to the current version of 11.0. As the version goes up, Microsoft has armed C# with handy features supported by powerful syntaxes such as LINQ (which stands for Language-INtegrated Query), generic programming, and lambda expression. Eventually, C# accomplished an empire of programming methodology where people from different nationalities communicated with different native tongues.

Unity adopted C# (pronounced as see-sharp) for its scripting language exposed to game developers and C++ for its internal implementation. Unity has favored C# for its simplicity and has been trying to maximize its functionality continuously through IL2CPP, DOTS, and many others. This turns out to be a reasonable strategy to boost productivity for game developers. Leveraging the strength of C# Reflection, Unity avoids boilerplate code appearing in Unreal that often leads to malfunctioning of Visual Studio Intellisense.

I have experienced several C++ projects, one of which was an AAA project with an in-house engine (to be honest, it was not an engine, but a jungle of Win32 and DirectX 9). It was full of macros and Python scripts for metaprogramming and suffered a long build time. If I could design my own game engine in the future, I would provide future C++ (compared to modern C++) as a scripting language only if it promises to be a programming language that can be directly used without a significant amount of modification. If that is not the case, I would still opt to add a C# layer for scripting upon the C++ engine core.

Other Development Tools

- Visual Studio for Integrated Development Environment (IDE)

- Git for version control

- GitHub for Git hosting service

- RenderDoc for debugging shaders

- Google Drive for sharing resources

How Peninsula is Programmed

Combined battlefield

Project Peninsula seeks a Combined Battlefield in which various combat units fight each other on a large-scale warfare scene. Followings are those combat units.

- Infantry

- Vehicles

- Tanks

- Other ground vehicles

- Aircraft

- Emplaced weapons (AA guns, howitzers, …)

- Structure (bunker, building, …)

As you can see, these groups are completely distinguished from each other in every aspect. As to mobility, for example, infantrymen run on their legs; tanks advance by looping their tracks; fighters propel either by rotating their propellers or bursting jet engines. The situation becomes even more complicated when interaction between different unit categories is considered. What should happen if a tank dives into a crowd of infantry? Should tanks be able to run over soldiers? If it should, what about armored cars?

It is no exaggeration that handling this complexity properly is the keystone to successful development. From the perspective of OOP, it is a matter of grouping entities into classes, encapsulating, and providing a common interface. As to the game architecture, it concerns segregating the code and the data. When it comes to general programming concepts, applying the right design patterns for the right situations counts.

Data-Driven Programming

In computer programming, Data-Driven Programming is a programming paradigm in which the code describes the data to be matched and the processing required rather than defining a sequence of steps to be taken directly. Discussions on [4] explain what data-driven programming is using pseudocode. Let’s apply this to a real-time strategy to compare a non-data-driven version and a data-driven version.

The very first code block demonstrates a non-data-driven way of movement of a tank with if statements.

if tank.name == "M26Pershing":

speed = 30

else if tank.name == "M4Sherman":

speed = 35

else if tank.name == "Tiger1":

speed = 25

tank.Move(speed)

Someone might point out that this is ill-formed from the perspective of OOP, so polymorphism with overridden functions is the right way to go.

speed = tank.GetSpeed()

tank.Move(speed)

...

class M26Pershing:

function GetSpeed():

return 30

class M4Sherman:

function GetSpeed():

return 35

class Tiger1:

function GetSpeed():

return 25

This solution follows the principle of OOP, but the side effect is that we have to add a new class to our project every time we extend the slot by one. Applying an even more strict coding rule, we will have to segregate each class just to grant each tank a different speed.

We now come up with a better idea: storing speed data in a key-value map (Dictionary in Python and C#, std::unordered_map in C++)

speedMap = {M26Pershing: 30, M4Sherman: 35, Tiger1: 25}

speed = speedMap[tank.name]

tank.Move(speed)

Yes! We added a new tank to the project by modifying only speedMap and is much easier than before, despite the necessity to recompile the entire codebase after the modification. Depending on the codebase’s architecture, recompilation should not be overly time-consuming. Nonetheless, it is essential to restart the game, and this is critical when we want to modify and test the value simultaneously. Additionally, it is very likely that the alteration is derived from a designer’s intention. However, in this case, it is a programmer who actually changes the value. The workflow should be better if the one who wants to modify data and the one who fixes the data coincides.

Data-Driven Programming addresses all the issues previously stated. In data-driven programming, program logic only defines how each stage behaves. What mandates the actual control flow is, roughly speaking, a text file external to the code. The program logic is given input files and carries out whatever is written in the texts. The code becomes relatively simple with data-driven programming.

speed = tank.ReadFromFile("speed")

tank.Move(speed)

Instead, the details are stored in a separate input file.

M26Pershing

speed: 30

...

M4Sherman

speed: 35

...

Tiger1

speed: 25

...

Peninsula keeps data in JSON format. JSON format facilitates a highly organized structure with objects and arrays. The syntax with key-value structure is readable and convenient to be edited in Microsoft Excel. Unity has a built-in utility to serialize and deserialize JSON format named JsonUtility.

Data for all the tanks in Peninsula are described in TankData.json as below.

...

{

"name": "Tiger",

"capacity": 5,

"minimum": 4,

"maxHealth": 2000,

"frontArmor": 1.0,

"rearArmor": 1.0,

"turretProperties":

[

{

"horizontalAimSpeed": 10.0,

"maxLeftAngle": 10.0,

"maxRightAngle": 10.0,

"verticalAimSpeed": 10.0,

"maxUpAngle": 10.0,

"maxDownAngle": 10.0

}

],

"moveForce": 50000.0,

"turnTorque": 6.0

},

{

"name": "M4A2_75mm",

"capacity": 5,

"minimum": 4,

"turretProperties":

[

{

"horizontalAimSpeed": 10.0,

"maxLeftAngle": 180.0,

"maxRightAngle": 180.0,

"verticalAimSpeed": 10.0,

"maxUpAngle": 10.0,

"maxDownAngle": 10.0

}

],

"moveForce": 50000.0,

"turnTorque": 6.0

},

{

"name": "M26Pershing",

"capacity": 5,

"minimum": 4,

"maxHealth": 2000,

"frontArmor": 1.0,

"rearArmor": 1.0,

"turretProperties":

[

{

"horizontalAimSpeed": 10.0,

"maxLeftAngle": 10.0,

"maxRightAngle": 10.0,

"verticalAimSpeed": 10.0,

"maxUpAngle": 10.0,

"maxDownAngle": 10.0

}

],

"moveForce": 50000.0,

"turnTorque": 6.0

},

...

This data is, in turn, deserialized into an instance of Data which is a thin wrapper of a list of instances of type T. LoadJsonFile loads a JSON file and returns an instance of type Data<T> converted from the content of the JSON file.

public static Data<T> LoadJsonFile<T>(string path, string fileName)

{

TextAsset jsonData = Resources.Load($"{path}/{fileName}") as TextAsset;

Data<T> data = JsonUtility.FromJson<Data<T>>(jsonData.ToString());

return data;

}

In this case, T is TankProperty, as we are loading data for tanks.

[Serializable]

public class VehicleProperty

{

public string name;

public int capacity;

public int minimum;

public float maxHealth;

public float frontArmor;

public float rearArmor;

public TurretProperty[] turretProperties;

public override string ToString()

{

return name;

}

}

[Serializable]

public class TurretProperty

{

// For the turret

public float horizontalAimSpeed;

public float maxLeftAngle;

public float maxRightAngle;

// For the gunshield;

public float verticalAimSpeed;

public float maxUpAngle;

public float maxDownAngle;

}

Finally, TankController directly references these to determine the engine power of a tank.

rgdbody.AddRelativeForce(Vector3.forward * controlVector.y * tankProperty.moveForce);

Designing VehicleController Class

Most game engines have recently been empowered by visual scripting systems. Unreal Blueprints provides an intuitive way for designers and artists to contribute to the game without deep coding knowledge. The intention behind this is to make it easier for developers other than programmers to build a game logic, thus dividing fixed code and design-oriented behavior more effectively.

Storing and loading data from a JSON file occupies only a very small portion of Peninsula’s data-driven approach. There is still a large portion of gameplay data that can’t be presented in numbers: behaviors specific to each tank. Unity provides an inspector to which members can be serialized, allowing designers to control not just the numerical values of components but also behaviors through GUI! Let me explain the process of designing the VehicleController class to make it clear what the interaction with the inspector looks like.

The first thing we have to consider is the class hierarchy of vehicles. The requirements are as follows.

- Vehicles have many common characteristics; that’s why they are categorized into ‘vehicles’! Therefore, it sounds reasonable that we define a superclass

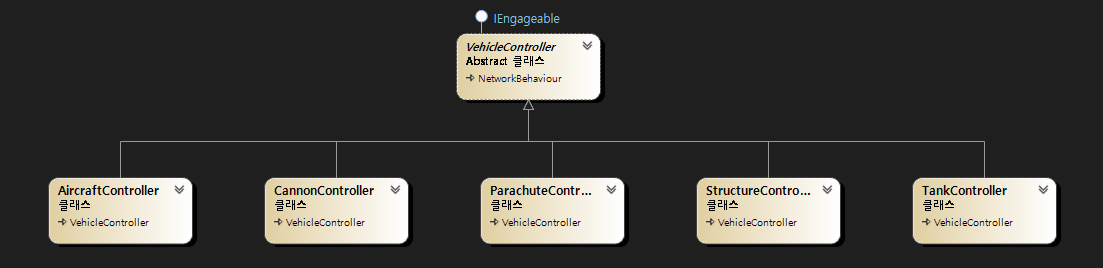

VehicleControllerand let specific kinds of vehicle classes (tank, aircraft, …) be derived from it. VehicleControllermust be an abstract class. That’s because every vehicle, in reality, falls into one of the concrete categories of vehicle rather than existing as a pure notion of ‘vehicle’.- Finally, I would like to refrain from deepening the hierarchy; we will end up with a deep, dark, and endless mine of classes at the end of continued vertical extensions.

The class diagram for the vehicle system reflecting these requirements looks like this.

Once the hierarchy is determined, we may now pay attention to the design of VehicleController itself. Being one of the basic concepts for the in-game combat system, designing the turret component properly is our primary concern. The types of turrets are as diverse as the types of vehicles. Our strategy is to embed common core features into the code and allow customization in the inspector so that we can reflect the variance among vehicles outside the code.

Through a case study, I came up with a few considerations before outlining the code.

- Turrets behave independently from each other and the hull. That is why modern vehicles are armed with turrets. A vehicle can attack multiple enemies at once by operating each turret separately.

- Turrets are heterogeneous. Tanks, for example, are generally installed with a single main turret and a few machine gun turrets.

- Turrets have the capability to rotate horizontally and vertically. The turret itself takes charge of horizontal rotation. Vertical rotation is achieved through a gun shield attached to the turret (in reality, it’s a mount that actually acts as a hinge).

- A turret can be armed with more than one weapon. Tanks usually have coaxial machine guns for measuring distances along with their main guns.

The T-28 was a Soviet multi-turreted medium tank used during WWII. A T-28 had three turrets in total, including one main turret with a 76.2mm gun.

The T-28 was a Soviet multi-turreted medium tank used during WWII. A T-28 had three turrets in total, including one main turret with a 76.2mm gun.

These are rationales for the presence of TurretController. One TurretController instance represents one turret of a vehicle and is directly attached to each turret GameObject. Eventually, this also affects the way a player controls a vehicle; a turret plays a role as an atomic controllable component. There is an analogy between ‘turret - vehicle’ and ‘squad member - squad’.

The weapons field is serialized to the inspector to allow designers to select which weapons belong to this turret. Why shouldn’t we get all the WeaponController components from children? That’s because a turret can have another turret as a child, so retrieving all the WeaponControllers from children will, in turn, retrieve weapons belonging to its child turret, too. This is not what we intended, so we have to manually clarify which weapon belongs to which turret through the inspector.

public class TurretController : MonoBehaviour

{

[SerializeField] private Transform _gunShield;

public Transform gunShield { get => _gunShield; }

...

[SerializeField] private WeaponController[] weapons;

...

public Transform aimTarget { get; private set; }

}

There is a has-a relationship between VehicleController and TurretControllrs, which reflects the fact that a vehicle can have multiple turrets under control.

public abstract class VehicleController : NetworkBehaviour, IEngageable

{

...

public TurretController[] turretControllers { get; private set; }

...

}

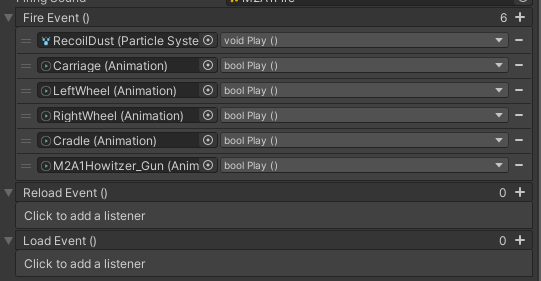

Delving more into the turrets, we ultimately arrive at the weaponry. Weapons entail several events upon firing, reloading, or loading, which differ weapon by weapon. Therefore, it is better to give designers options to customize those actions. I personally use UltEvents [5] asset, which provides more functionality than the Unity built-in UnityEvent, to expose events to the inspector.

public abstract class WeaponController : MonoBehaviour

{

...

[SerializeField] private UltEvent _fireEvent = new UltEvent();

public UltEvent fireEvent { get => _fireEvent; set => _fireEvent = value; }

[SerializeField] private UltEvent _reloadEvent = new UltEvent();

public UltEvent reloadEvent { get => _reloadEvent; set => _reloadEvent = value; }

[SerializeField] private UltEvent _loadEvent = new UltEvent();

public UltEvent loadEvent { get => _loadEvent; set => _loadEvent = value; }

...

}

Using these configurable callbacks on the inspector, designers may choose which events to invoke according to their intent. The moment M4A2 fires a shell, dust erupts, and the whole body retreats violently. The barrel bounces backward and then forward as a result of recoil. All the events are figured through the GUI instead of the fixed script, eventually bringing more flexibility.

Combining all these considerations, various vehicles can demonstrate their own maneuvers as shown in the linked trailer (M4A2 howitzers appear from to).

Design Principles

Why Is It Needed?

In software engineering, Design Principles are fundamental guidelines and best practices that guide programmers in designing good software structures. In fact, you can write software without knowing design principles. Roughly speaking, a program is merely a set of loops and branches. When we were novice programmers, we didn’t have room to consider what good design is. We were busy making our code at least launch.

As we grow up as software engineers, we read and write larger and larger programs, often encountering spaghetti code. Then, we start to deliberate which one is the correct way to write a program among many paths: to make a member private or public. Polymorphism or branch? To copy or to functionize? The time flows on and on, and we finally get a professional software engineer position. The codebase goes beyond millions of lines. It isn’t possible anymore for a single programmer to understand the entirety. In this circumstance, we can’t maintain the product without establishing common rules.

Design principles are not something completely new. We know them a priori as we develop as a software engineer. They are standardized principles many ancestors found worth naming. Following design principles enhances readability and troubleshooting is made easier. But best of all, design principles help us preserve the unity of the codebase. Although building software together with others is a tough task, we can alleviate those difficulties by learning and applying design principles.

To enjoy all the benefits design principles bring, I have considered design principles during planning steps before I actually type code. Of course, this pertains to Project Peninsula. The two most critical patterns applied to the project are the SOLID principle and the DRY principle.

DRY

DRY Principle, which stands for Don’t Repeat Yourself, is a programming concept advocating for the avoidance of code duplication. The principle emphasizes that each piece of knowledge or logic within a system should have a single, unambiguous representation. In other words, any piece of functionality or information in a software project should not be repeated.

The DRY principle is a materialization of the famous saying, “Do not write duplicated code”. The necessity of modularizing duplicated code arises as the codebase enlarges. Suppose we try to modify all the ‘duplicated’ parts in the code. For a tiny toy project, we know where all those parts are, and we can properly catch them up, although the danger of missing one still remains. With a gigantic commercial project, we will miss a lot, yielding fragmentations in the codebase.

Therefore, we conclude that we refrain from producing repetitive code according to the DRY principle. But… to which extent? Should we modularize every single duplication appearing? The DRY principle, like many other programming principles, should not be taken as absolute. While developing Peninsula, I made a few mistakes of over-modularization by writing these kind of methods. Here is an example where modularization impeded debugging.

public void ActionMoveAction(Action doBeforeMovement, Action doAfterMovement) // Delay - Invoke doBeforeMovement - Move until the breaking distance - Invoke doAfterMovement

{

StartCoroutine(OrderDelayCoroutine());

IEnumerator OrderDelayCoroutine()

{

doBeforeMovement?.Invoke();

yield return new WaitUntil(() => agent.hasPath && agent.remainingDistance <= BRAKING_DIST); // Wait until the infantryman reaches the destination

doAfterMovement?.Invoke();

}

}

ActionMoveAction takes two delegates as parameters: doBeforeMovement and doAfterMovement. After invoking doBeforeMovement, it waits until the agent has reached the destination, followed by the invocation of doAfterMovement. ActionMoveAction found its places where this kind of ‘do something - move - do something’ pattern emerged. The Embark method used to be such one.

public void Embark(VehicleController vehicleToEmbark, int seatID)

{

SetDestination(vehicleToEmbark.GetEntrance(seatID).position);

// Stop engaging

Action before = () =>

{

if (!engaging) return;

CeaseFire();

Ease();

};

Action after = () =>

{

vehicleToEmbark.GetOn(this, id);

};

DelayedAction(() => { ActionMoveAction(before, after); });

}

Unfortunately, it turned out that I managed to remove duplicated logic, but not in a meaningful way. Embark makes a squad member stop engaging, run, and then embark on a vehicle upon arriving. However, realizing that this method does so at a glance is difficult, as SetDestination is apart from yield return new WaitUntil(() => agent.hasPath && agent.remainingDistance <= BRAKING_DIST); inside ActionMoveAction. Instead, the unrolled plane expressions are much more easy to understand.

public void Embark(VehicleController vehicleToEmbark, int seatID)

{

StartCoroutine(EmbarkCoroutine());

IEnumerator EmbarkCoroutine()

{

// Stop engaging

if (engaging)

{

CeaseFire();

Ease();

}

SetDestination(vehicleToEmbark.GetEntrance(seatID).position); // Move to the vehicle

yield return new WaitUntil(() => agent.hasPath && agent.remainingDistance <= BRAKING_DIST); // Wait until the infantryman reaches the destination

vehicleToEmbark.GetOn(this, id);

}

}

The DRY principle often collides with expressiveness in many cases [6]. Sometimes, plain, explicitly narrated statements are easier to understand and maintain than modularized structure despite the danger inherent to duplication. When to apply and when not to apply the DRY principle depends, and here is a rule of thumb: it is better to modularize only if doing so is meaningful and makes sense.

SOLID

SOLID is an acronym that represents a set of five concrete rules of object-oriented programming. Robert C. Martin introduced these principles and are widely adopted by practitioners. The SOLID principles are [7]:

- Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) - A class should have only one reason to change.

- Open/Closed Principle (OCP) - Software entities should be open for extension but closed for modification.

- Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) - Subtypes must be substitutable for their base types without altering program correctness.

- Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) - No code should be forced to count on methods it does not use.

- Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) - High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions, and abstractions should not depend on details.

Project Peninsula adheres to the SOLID principles. Rather than direct application, adherence to rules is achieved through the integration of Design Patterns. Design patterns are a toolkit of solutions to common problems in software design. Design patterns suggest orthodox solutions whenever we are about to fall into the temptation of spaghetti code.

Strategy Pattern is the most frequently used pattern in Project Peninsula. The strategy pattern is a behavioral design pattern where algorithms are encapsulated into separate classes, allowing clients to interchange algorithms dynamically without modifying the structure. The weapon system in Peninsula is implemented with the strategy pattern to benefit from the flexibility of switching the mechanism hired by weapons.

Weapons in Peninsula are categorized into three types according to their actions: full-auto, semi-auto, and single-action. Each type comprises a class that inherits from WeaponController, an abstract class that presents a general weapon.

public abstract class WeaponController : MonoBehaviour

{

...

protected abstract IEnumerator Fire(); // Override this with a concrete internal firing mechanism

...

}

public class FullAutoWeaponController : WeaponController

{

...

protected override IEnumerator Fire()

{

// Internal firing mechanism of a full-auto weapon

...

}

}

public class SemiAutoWeaponController : WeaponController

{

protected override IEnumerator Fire()

{

// Internal firing mechanism of a semi-auto weapon

...

}

}

public class SingleActionWeaponController : WeaponController

{

protected override IEnumerator Fire()

{

// Internal firing mechanism of a single-action weapon

...

}

}

Firearm prefabs are associated with one of FullAutoWeaponController, SemiAutoWeaponController, or SingleActionWeaponController, depending on the mechanism of the model. Upon a soldier being armed with a firearm, he is granted nothing more than an instance of WeaponController. The actual behavior is abstracted from the shooter’s perspective. All that a shooter does is to invoke PullTrigger on WeaponController.

public class InfantryController : MonoBehaviour

{

...

public void SetFirearm(WeaponController _weaponController)

{

// ========== Set firearm information ==========

weaponController = _weaponController;

...

}

...

private IEnumerator FireCoroutine()

{

while (true)

{

weaponController.PullTrigger(remainingHorizontalAngle < AIM_ROTATION_THRESHOLD);

yield return new WaitForSeconds(TRIGGER_CHECK_CYCLE);

}

}

...

}

Although there is no judgment made whether the weapon is full-auto, semi-auto, or single-action, soldiers can be armed with various weapons of different behaviors through a single call to SetFirearm.

From the perspective of SOLID,

- The strategy pattern adheres to the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) by separating the responsibility of object usage and implementation.

- It follows the Open-Closed Principle (OCP) by being open for extension and closed for modification in functionality.

- By allowing the substitution of implementations (overrides) in subclasses for the

Firemethod of the parent type, it obeys the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP). In fact,WeaponController.Fireis an abstract method, therefore greatly reducing the risk of violating the LSP. - The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) is observed as the interface defines a method for firing a weapon without including unnecessary methods used by other clients.

- Avoiding direct dependency on implementations by abstracting types through interfaces ensures loose coupling, supporting the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) and allowing runtime method changes without strong coupling between objects.

There are many more beneficial design patterns yet to be discussed, but I can’t enumerate all of them here. Another favorite design pattern of mine is the Observer Pattern. Please refer to this post to learn more about the observer pattern applied to our project.

Optimization

When to take the optimization stage is one of major concerns of all software engineers. Optimizing early is likely to be too rash; it might be overwritten later or could even bring backfire on the performance. On the other hand, optimizing at the final stage is likely too late; it requires the entire code to be rewritten. Rather than selecting a specific timing, we ought to draw general optimization strategies.

- The reason for planning arises again.

- Fortunately, serious bottlenecks are evident enough to be predictable from the planning step.

- For instance, if you anticipate an occurrence of nested triple for loop, it is high time you search for an alternative algorithm.

- If you expect an IO for every frame, you have to expect caching, too.

- Keep general optimization rules in mind.

- There are numerous pieces of advice about optimization. They could be specific to C# or Unity or belong to the domain of software engineering in general.

- General rules are called such because they are easily applicable and effective for various situations. By recalling and subsequently applying general rules, we can mitigate the risk of mature or belated optimization.

- Here are some optimization keywords shared among software engineers.

- Caching repetitive actions

- Reducing garbage to be collected by GC

- Restricting draw calls by batching

- Maximizing cache locality

- Utilizing profilers (Unity Profiler, for example) to search for bottlenecks

- Graphics optimization (lightmapping, light probing, …)

- The hierarchical approach works for optimization.

- The approach begins by realizing the weights of timings in a game are not equivalent. There are four timings in a game: initial loading, stage loading, and occasional or every frame during gameplay.

- One second of delay during the initial loading is negligible; the same amount of delay during a stage loading is noticeable. Again, the one-second delay occasionally during gameplay is sufficient to completely spoil the gameplay experience; with the same delay per every frame, would you still call it a ‘game’?

- This discrepancy between timings mandates that we put emphasis on more frequent tasks. Whenever possible, we can present players with more pleasant play experiences by bringing forward tasks during gameplay to the loading step, prefetching required data, and saving IOs at playtime.

- Object pooling is a technique where reusable game objects are pre-instantiated and kept in a collection, allowing them to be efficiently reused instead of repeatedly creating and destroying instances during playtime.

- As a matter of course, pre-instantiated objects occupy memory space. If the pool size is set too high, it might lead to unnecessary memory consumption. It is crucial to carefully pick pooled targets in this scenario.

- Novel techniques!

- Hiring novel techniques might dramatically skyrocket the performance.

- One kind of ‘novel technique’ is compute shader, which is often employed to offload certain computational tasks from the CPU to the GPU, taking advantage of the parallel processing capabilities of modern graphics hardware. FOV Mapping takes advantage of GPU computing.

Multiplayer

The multiplayer system of Project Peninsula is being implemented using Mirror Networking. Unity Mirror is a high-level, open-source networking solution for Unity game development. It simplifies multiplayer implementation by offering features like replication, RPCs, and support for various network topologies via attributes and components.

The project aims to utilize dedicated servers. Dedicated servers replicate game environments just as singleplayer clients do. To engage with the game, players need to connect using distinct clients, establishing a connection to the server for interacting other players.

Most gameplay logic that should be synchronized among players takes roundtrips with three major stages:

- A client-side method reacts to a player’s input. The input data is subsequently transferred to the server.

- The server undertakes critical logic with the processed input, ensuring fairness among users. It returns the consequences of the execution to the client.

- The client reflects the outcomes the server sends to the components visible to the player.

Below, we will briefly outline how a squad starts engagement with the enemy across the server.

- The client detects a tapping input from the player’s device. The

[Client]attribute denotes thatOnSingleTapis executable only on clients.OnSingleTapin turn, invokesEngageCommand, passing a net ID to identify the targeting enemy unit.[Client] private void OnSingleTap(InputAction.CallbackContext context) { ... EngageCommand(-1, engageableSquad.GetNetID(), -1); ... } -

EngageCommandis marked as[Command]which allows Remote Procedure Call (RPC) from the client to the server.EngageCommandinitializes the engagement status and propagates throughout with a call to a set of...RPCmethods.[Command] public void EngageCommand(int memberID, uint enemyID, int enemyMemberID) { ... // Find the enemy corresponding to enemyID IEngageable enemy = NetworkServer.spawned[enemyID].GetComponent<IEngageable>(); ... // ===========Set the status on the server =========== SetEngageStatus(myMemberIDs, enemy, targetEnemyMemberIDs); ... // =========== Order on the members =========== SetTargetOrderRPC(myMemberIDs, enemyID, targetEnemyMemberIDs); AimOrderRPC(myMemberIDs); CommenceFireOrderRPC(myMemberIDs); } - Again, we labeled

SetTargetOrderRPCas[ClientRpc], hoping that we could invoke an RPC from the server to the client with it.SetTargetOrderRPCconveys the server’s processing outcome to the game’s ‘motional’ status.[ClientRpc] private void SetTargetOrderRPC(int[] myMemberIDs, uint enemyID, int[] targetEnemyMemberIDs) { ... else { for (int i = 0; i < myMemberIDs.Length; ++i) { IEngageable enemy = NetworkClient.spawned[enemyID].GetComponent<IEngageable>(); Transform[] targetTransforms = enemy.GetTargetTransforms(targetEnemyMemberIDs); squadMembers[myMemberIDs[i]].SetTarget(targetTransforms[i]); } } }

Conclusion

It was a long story, wasn’t it? The development of Project Peninsula has not yet been completed. There are still a lot of modules waiting to be programmed, including the game management system. The game still needs to be prepared with matchmaker, community features, and other server infrastructures. And we can easily predict that they cannot easily be written. Frankly speaking, I can’t anticipate the number of obstacles I will be facing in the field of software engineering.

Despite surpassing the typical scale of a personal project, I believe the project has been established upon the stalwart bedrock so that the project’s growth is charged with a sufficient amount of fuel. The project adheres to established coding rules, design patterns, and principles, ensuring immediate functionality, long-term maintainability, and scalability. When that alone is not sufficient, I can benefit from Unity’s extensive community support.

As I accumulate experience as a software engineer, Project Peninsula progresses further. The client and server logic are significantly expanding and being optimized simultaneously. The visual effects are also getting more stylish, drawing more potential strength from the evolving graphics hardware of recent mobile phones. More surprisingly, these accomplishments are being shared via Unity Asset Store, gaining popularity every day. Distributing project modules will drive the project to be composed of more modular compositions.

There are a number of tales I still need to address. More detailed discussions will be in separate posts, so please keep an eye on my website. Thanks for reading!

References

- [1] https://blog.unity.com/engine-platform/unity-and-net-whats-next

- [2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C_Sharp_(programming_language)

- [3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Data-driven_programming

- [4] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/1065584/what-is-data-driven-programming/

- [5] https://assetstore.unity.com/packages/tools/gui/ultevents-111307

- [6] Grimm, R. (2022). C++ Core Guidelines Explained: Best Practices for Modern C++ (1st ed.). Addison-Wesley Professional.

- [7] Joshi, B. (2016). Beginning SOLID Principles and Design Patterns for ASP.NET Developers (1st ed.). Apress.

- [8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Game_server

Leave a comment